India's key strength is its favourable demography - the average age of its population will be 29 years in 2020. The demographic dividend translates into growth in several ways. It holds the promise of an expanding middle class, affordable labour force, productivity growth, and thereby giving rise to greater economic growth. These dynamics also indicate that India holds an important place in the global education industry with one of the largest networks of higher education institutions in the world. But the challenge for Indian higher education is that it does not necessarily translate into jobs; thereby calling for a significant transformation.

Over the last two decades, India has remarkably transformed its higher education landscape. It has one of

the largest networks of higher education institutions in the world. With well-planned expansion and a

student-centric learning-driven model of education, India has not only bettered its enrolment numbers but

has dramatically enhanced its learning outcomes. As a result, today, India's 70 million student population is

a force to reckon with. Among them are potential thought leaders, researchers and academicians –

positioned at the helm of knowledge creation. Among them are entrepreneurs and executives of the future,

industry-ready and highly sought after. From among them emerges India's massive workforce, the engine of

its US$13 trillion economy.

Despite these strides of progress, India's higher education institutions are not yet the best in the world – India

has fewer than 25 universities in the top 200. The promise of excellence and equity i.e. the challenge to

provide higher education in cost-effective ways to lead to employment is still a cause for concern to the policy

makers.

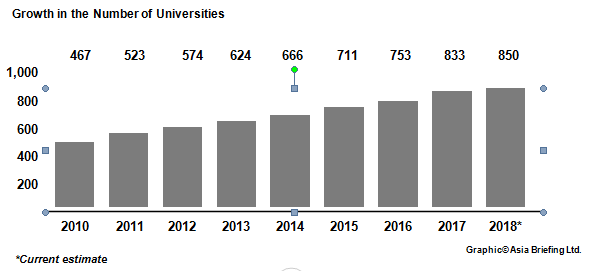

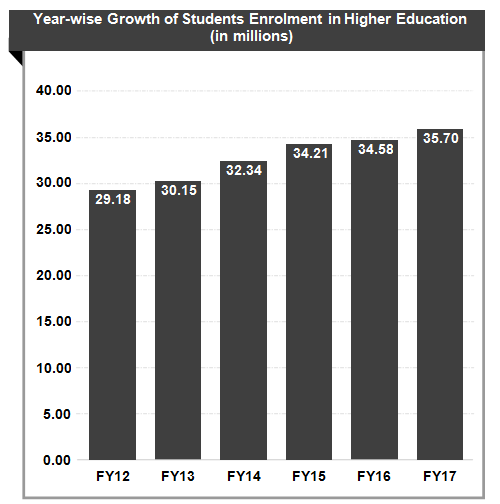

With both the Government and the private sector stepping up to invest in the Indian education sector, the number of schools and colleges have seen an uptrend over the past few years. The Government's initiative to increase awareness among all sections of the society has played a major role in promoting higher education among the youth. The number of colleges and universities in India reached 39,050 and 850, respectively in 2017-18 and India had 35.70 million students enrolled in higher education in 2017.

Source: UGC Annual Report 2015-16, UNESCO Global Education Digest 2010, MHRD Annual Report

With almost 45 percent of its population under the age of 25 years, India confronts a massive challenge of increasing access to quality educational institutions to facilitate economic growth in the country. Also the growth of higher education needs to be in direct proportion to employability to ensure economic growth.

While India has made significant progress in ensuring access to primary education, the proportion of

students who remain in the education system until higher education is considerably less. The paper will study

the present scenario of higher education in India with emphasis to the following parameters:

• Economics of higher education in India.

• Higher education & employability.

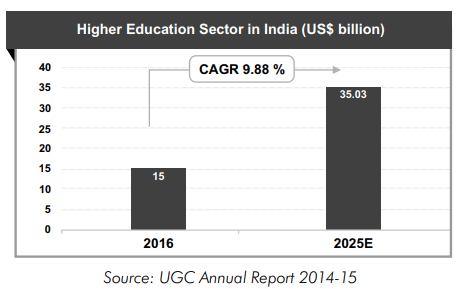

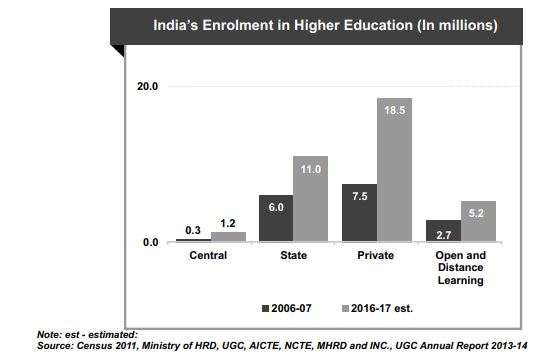

The education sector in India is poised to witness major growth in the years to come as India will have world's largest tertiary-age population and second largest graduate talent pipeline globally by the end of 2020. The sector is estimated to reach US $ 144 billion by 2020 from US $ 97.8 billion in 2016. Higher education sector in India is expected to increase to US $ 35.03 billion by 2025 from US $ 15 billion in 2016. Around 35.7 million students were enrolled in higher education in India during 2016-17. Government target of Gross Enrolment Ratio (GER) of 30 per cent for higher education by 2020 to drive investments. The spending in higher education sector is expected to grow at 18 per cent from ` 46,200 crore (US $ 6.78 billion) in 2016 to reach ` 232,500 crore (US $ 34.12 billion) in the next 10 years.

Through the expansion of the education sector in India over the years, most of the Universities were public

institutions with powers to regulate academic activities on their campuses as well as in their areas of

jurisdiction through the affiliating system. However, over the years the government expenditure on

education, as a percentage of the GDP, has been decreasing consistently. Six years ago, i.e. in 2012-13,

education expenditure was 3.1% of the GDP. It fell in 2014-15 to 2.8% and registered a further drop to 2.4%

in 2015-16 and 2.6% in 2016-17.

However, given the limited resources, the Government is consistently trying to improve the situation. There

has been a significant increase in the share of the state private universities as part of total universities from

3.43 per cent in 2008-09 to 34.82 per cent as of April 2018. Nearly 22 million students (65%) are enrolled

in private institutions in various courses.

While the government-owned institutions for higher education increased from 11,239 in 2006-07 to 16,768 in 2011-12 (49%), private sector institutions recorded a 63% growth in the same period from 29,384 in 2006-07 to 46,430 in 2011-12, according to the 12th five-year plan document of the erstwhile Planning Commission. This proliferation of large number of institutions has not necessarily translated into higher employment.

The irony is that despite increasing enrolment in higher education, educational opportunities and traditions that

Indian Universities have built up, since independence have been able to produce graduates, capable only of pursuing

limited careers, but, in the new globally competitive environment that is emerging in the country, the Indian

student is now required to develop a multifaceted personality to cope up with the rapid changes in the world at

large. While these changes are being incorporated into certain higher education courses with visible effects there

still is a long way.

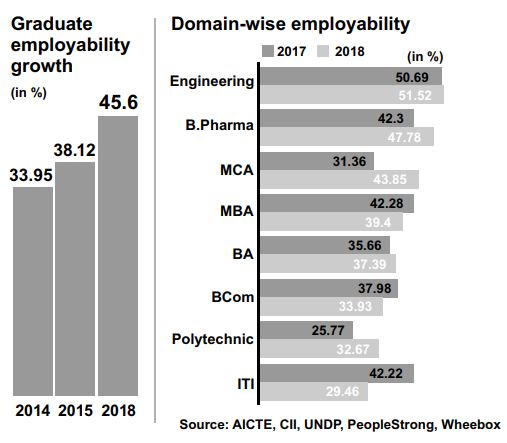

According to the India Skills Report 2018, employability score has taken a big leap as compared to last year. Since

2014, overall employability among graduates has risen from 34% to 46%, a jump of more than 35%.

In other words, nearly one out of two fresh graduates are employable now, up from one out of every three

four years back. Fresh engineers, often termed largely unemployable, were found to have 52%

employability. Within the engineering domain, those pursuing computer sciences have the highest

employability, says the report that surveyed 510,000 students and 120 companies.

Though the scenario has shown a definite improvement in employability in certain fields, the employability of graduates of management institutes, Industrial Training Institutes (ITIs) and bachelor in commerce are showing a negative trend. It suggests that though, most of the time, the problem is not the availability of the job, but the mismatch or lack of skills to carry out a particular job. Therefore, it is important to develop skilling models, which will not only address the issue of the need for skilled human resources but will also provide employment to the bottom of the pyramid.

The education sector has seen a host of reforms and improved financial outlays in recent years that could

possibly transform the country into a knowledge haven. But the present situation of rapidly increasing

enrolment in higher education without improving employability is to be addressed urgently. In order to avoid

increased unemployment among young graduates, more focus should be placed on quality and labor

market needs. The key is to ensure continued collaboration between employers and universities and to pay

attention to the changing needs of businesses. Employers can then take advantage of graduates who have

the skills and capabilities to drive their productivity and future success.

Merely filling the number of people trained in different trades is not the key to reap the benefits of the

country's demographic dividend – the trained personnel should be able to find a decent productive job.

Therefore, job creation should be considered as a parallel process, along with skill development. A twopronged

approach emerges to unleash the force of this much-touted demographic dividend. One, skilling

youth in both the farm and non-farm sectors in order to provide requisite skills to learners at each level of

education and experience, and two, accelerating entrepreneurship and self-employment in pace with GDP

growth, sufficing to absorb the new workforce each year.

It is expected that the aging economy phenomenon will globally create a skilled manpower shortage of

approximately 56.5 million by 2020 and if we can get our skill development act right, we could have a skilled

manpower surplus of approximately 47 million. The Skill India Mission with the Prime Minister at the Apex,

coupled with a framework to deliver training programmes in the non-formal sector, and a system that will

boost entrepreneurship and self-employment can lead India to become the Human Skills Factory of the

world, bridging the gap between higher education and employability!